Mike McCormick was talking about the unlikely meeting of a bumble bee and a bear.

Actually, he was reading aloud about characters featured in a children’s book. McCormick was connected online via Zoom with a boy of kindergarten age who followed along with him. They could see each other, as well as an electronic version of the illustrated book that highlighted printed words as they were spoken.

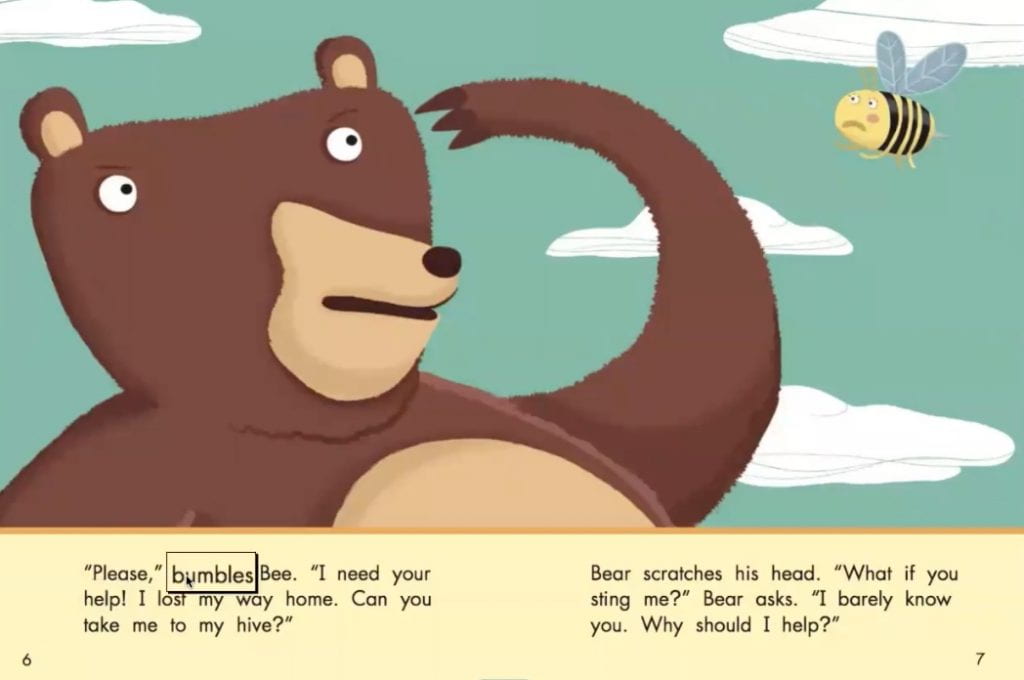

An image from the online version of the book “Let’s Bee Friends.”

McCormick, a member of the Osher Lifelong Learning Institute at UMass Boston, wasn’t reading with a grandson or anyone he had even met until recently. He was participating in an innovative pilot project initially developed to help two kinds of people who often struggled with the limitations imposed on daily life by the COVID-19 pandemic – young children and older adults.

The intergenerational tutoring project is managed jointly by the Department of Applied Psychology at Northeastern University’s Bouve College of Health Sciences and the Gerontology Department at UMass Boston. It started small this spring with five students and is gearing up for a second, bigger phase intended to reach 10 times as many students.

The ultimate goal is to create a refined model that helps older adults connect online with children for educational purposes on a much larger scale across the country. Project leaders believe the program can deliver online experiences that will remain valuable well after the COVID-19 threat has fully passed. But it was the shock of the pandemic that first got the concept off the drawing board and onto screens.

Jessica Hoffman

“There were these diverse needs in different age groups,” said Jessica Hoffman, a professor at Northeastern who is leading the project. “These needs came together through the power of Zoom so we could connect older adults with kids and help create better access to educational activities.”

The diverse needs were clear. Older adults who isolated themselves as much as possible to guard against the deadly health risk were kept from the people and routine activities that animated their normal lives. Isolation, loneliness and sometimes a sudden lack of purpose were common experiences.

Young children were also at home, unable to participate in anything resembling a normal school life. Those who needed extra help developing basic educational skills were at a particular disadvantage.

Hoffman, whose work has focused on school psychology, was very familiar with the educational frustrations of parents and young children created by the pandemic. She was also well aware of problems facing isolated older adults and the talents among members of the OLLI program, due in part to the fact she is married to Edward Alan Miller, chair of the UMass Boston Gerontology Department.

Hoffman contacted Jim Hermelbracht, director of the OLLI program at UMass Boston, and started talking about ways to get members interested in becoming tutors for the initial phase of the program. He pitched the idea in the institute’s weekly newsletter and got about 20 initial responses. That group would shrink to about 12 and eventually nine members were designated as tutors for the program (only five actually served in that role due to a limited number of available students).

Jim Hamelbrecht

One aspect that particularly appealed to those members: Project managers brought tutors into the process of designing the program, soliciting their feedback about which ideas worked best in practice and what should be changed.

“They really took into consideration a lot of questions and ideas OLLI members had in shaping the pilot program,” said Hermelbracht. “Members were really invested in giving shape to what they were going to be doing.”

Five of the nine tutors were former teachers. That included McCormick, who retired about nine years ago after spending more than two decades teaching kindergarten and first grade students in Milton.

Like all the online tutors, McCormick was working with a young child on basic reading skills. Those efforts were focused on letter-sound fluency skills as well as vocabulary development through a process of dialogic reading – which involves the adult reading aloud, asking questions, listening to responses and helping the child become a storyteller (Do you think the bear should help the bee?).

McCormick found the technology aspects of the project most challenging. He was connecting by Zoom but also using an online tool called Tutoring Buddy when working on letter-sound skills and then turning to another that provided the online book that appeared on their screens. Managing all those resources, while teaching and connecting with a child, took some practice.

In fact, tutors practiced with each other to develop and refine those skills. They all met online on Fridays with project managers to talk about what was going on in individual sessions with their students.

Among the practical things they discovered: Real-life complications made the original schedule hard to keep. Sessions originally expected to take about 15 minutes commonly stretched to a half hour. The plan for four weekly sessions was sometimes trimmed to three per week due to other commitments the children and their families needed to keep. Sometimes, it proved difficult to keep a restless young child focused in an online conversation.

Mike McCormick as he appeared via Zoom during one tutoring session

McCormick said it was clear his student had gained new reading skills and the Tutoring Buddy’s data-tracking confirmed that. But he said it was also important to encourage the child’s sense of himself as a learner. From the tutor’s perspective, it was a positive experience.

“I enjoyed meeting him and the conversation,” said McCormick. “Children are always surprising to me. They have their own ways of seeing things and they see things you don’t. I always found it interesting what they saw and how they perceived things.”

Hoffman said she hopes the tutoring program could eventually expand for use across the country. Even as COVID-related social restrictions fade, the online interaction between older adults and children who need help learning can still be a valuable experience for everyone involved.

“We’re really interested in developing a model that be scaled up for all 124 OLLI groups around the country in every state,” she said. “First we need to do more work shoring up the model and continue to do research with the ultimate goal of disseminating it more broadly.”

October 18, 2021 at 1:47 pm

A very similar program was offered in conjunction with the Ipswich Council on Aging and Winthrop Elementary School in Ipswich. Instructor Melissa DAndrea managed the program with approximately fifteen adult volunteers, teachers and multiple students. It was an amazing intergenerational project that was beneficial to all.

November 17, 2021 at 7:40 am

like me as a preschool tutor has also encountered difficulties reaching with my students because of this pandemic. And I am glad that we are going back to normal.