Vincent Mor is a leading academic expert on eldercare issues and a national authority on research related to nursing homes. The Brown University professor has been principal investigator in more than 40 grants funded by the National Institutes of Health that focus on the use of health services and the outcomes experienced by frail and chronically ill persons.

Mor and Susan Mitchell of Hebrew SeniorLife are leading an ambitious new collaborative research incubator for “pragmatic clinical trials” that test and evaluate interventions for Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias. Last month, they received a grant from the National Institute on Aging expected to total $53.4 million to fund that work over the next five years. It was one of the largest federal grants ever awarded for Alzheimer’s care.

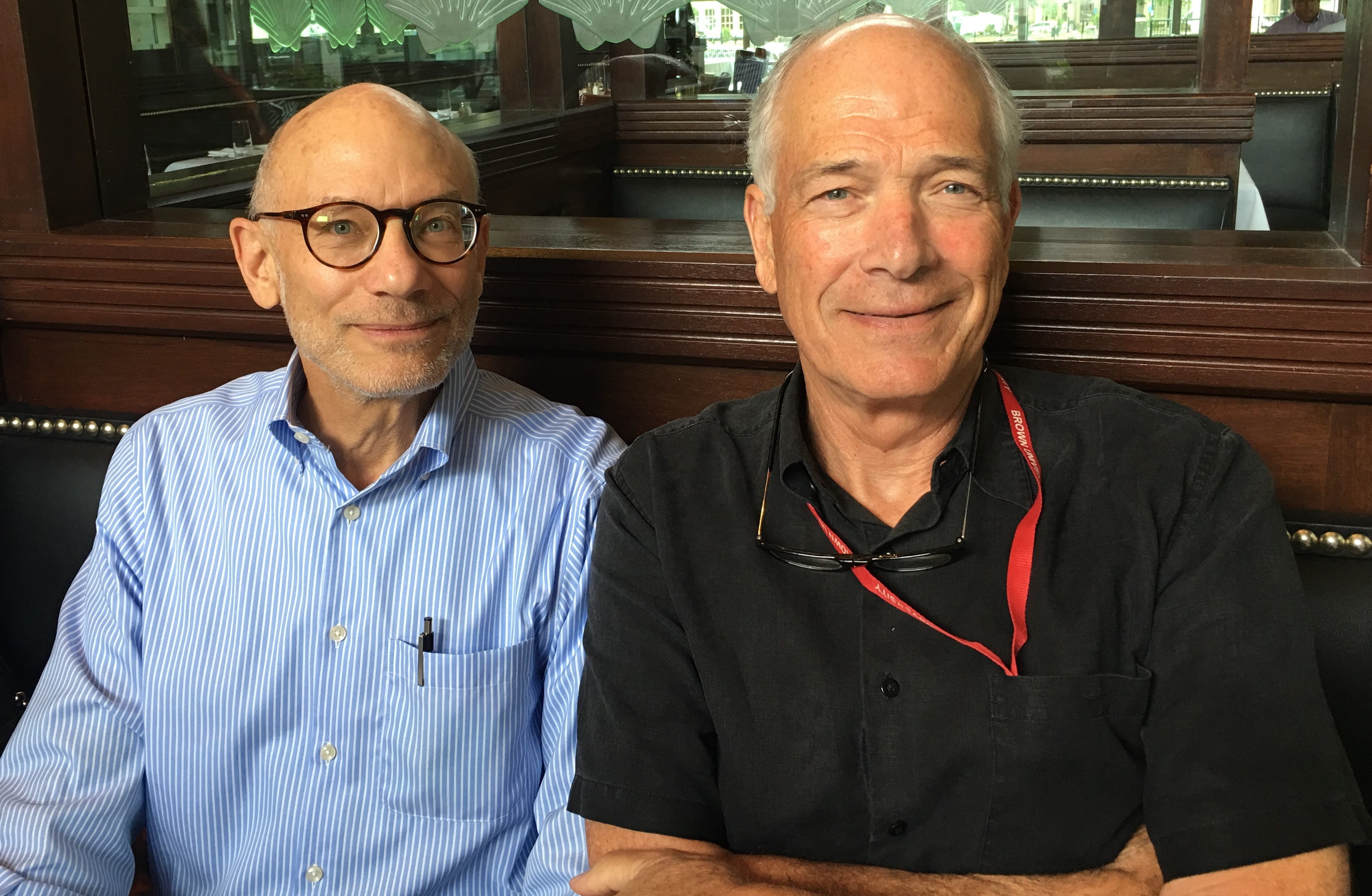

Gerontology Institute Director Len Fishman recently spoke with Mor to talk about his new project and discuss the state of the struggling nursing home industry. The following is an edited version of their conversation.

Len Fishman: You’ve just taken on a huge and ambitious project funded by the National Institute on Aging. Describe the scope of that project and the goal of that work.

Len Fishman: You’ve just taken on a huge and ambitious project funded by the National Institute on Aging. Describe the scope of that project and the goal of that work.

Vince Mor: The goal is to create an infrastructure that solicits, funds, supports, monitors and then hopefully launches up to 40 different pilot projects. We want to take ideas that seem efficacious when run by researchers — ones that help improve the quality of life and experiences of persons living with dementia and their caregivers – and imbed those interventions into functioning healthcare systems. I’m talking about everything from health plans to doctors’ offices to hospitals, nursing homes, assisted living facilities and daycare centers.

Vince Mor: The goal is to create an infrastructure that solicits, funds, supports, monitors and then hopefully launches up to 40 different pilot projects. We want to take ideas that seem efficacious when run by researchers — ones that help improve the quality of life and experiences of persons living with dementia and their caregivers – and imbed those interventions into functioning healthcare systems. I’m talking about everything from health plans to doctors’ offices to hospitals, nursing homes, assisted living facilities and daycare centers.

LF: You describe these pilots as “imbedded pragmatic clinical trials.” Explain what that means.

VM: These are trials in which interventions that seem to work when done by researchers, are piloted in real world settings to see if they can be engineered into the daily practice and operating procedures of places like emergency departments and nursing homes.

LF: Imagine you are looking back on this five to seven years from now. What would success look like?

VM: Let’s say half the pilots are actually able to do the human engineering that could make it possible for a health care system or a nursing home company to say, “Yes, I can find the business case for doing that. I’m ready and willing to actually move forward to a full-blown pragmatic trial imbedded in our health care system.”

LF: Let’s turn to nursing homes. Think for a moment about what a typical nursing home looks like today and describe that.

VM: A typical 120-bed nursing home would be owned and operated by a moderate-sized corporation with 10 to 30 facilities. If it is well-functioning, there will be a relationship with one or two local hospitals. There might even be a designated nurse or clinician working directly with hospital discharge planners to get people coming directly to the facility, where they provide therapy – OT, PT – six or even seven days a week. The front of the house will be post-acute care, and the back of the house will be long-term care. Among the 60 long-term care beds there, if they are lucky, 10-15 will be private pay. The rest will be Medicaid.

LF: Nursing home industry advocates claim the shortfall of Medicaid reimbursement compared with the cost of providing care has grown to $22 per day for each resident. That adds up to $8,000 a year. Do you agree the shortfall has reached that level?

VM: It depends a lot on what state you’re in. Payment rates in New York are much, much higher than in some other states. Minnesota and a few other states are higher than the state averages. But let’s say that the Medicaid payment rate is going to be something like $450 a day for a high case mix. If you’re in upper Manhattan, a hotel room will cost $380 if you’re lucky. So, just do the math. Imagine you’ve got 500 people at $400 dollars a day in a building in Manhattan, It’s just not a viable business, because those 500 people are sick patients.

LF: We have what would seem to be a paradox, a rapidly increasing population of older adults, especially 85 and over, but an actual reduction in nursing home beds nationally, with some very steep declines in certain states. In Massachusetts, for example, 214 nursing homes have closed since 2000. Do you foresee this trend continuing?

VM: For a little while, yes. If you put together assisted living beds and nursing home beds, then calculate them per thousand of elderly age 65 and over, we’re at about 5.5 to 6. It’s about 3.5 nursing home beds and 2.5 assisted living type beds. So there’s been this mass substitution of one venue for another, product differentiation by preference and money.

The nature of the nursing home will continue to change. The question for nursing homes: What is your mix of post-acutes and sub-acute stepdown versus very sick, very behaviorally compromised patients and what’s the right way to pay for that? Those are fundamentally important policy questions.

LF: What role do you think nursing homes will play five to 10 years from now?

VM: I believe that hospital beds will decline dramatically. Those people who have surgery or require short stabilizations post-stroke, post-breakage, post-whatever will be placed into some form of post-acute care. What are now our nursing homes will become these step-down units.

LF: What about the traditional long-stay nursing home resident?

VM: Those same nursing homes, in the back room, and some specialty nursing homes that don’t do rehab, will take those patients on vents, on continuous IV drip, with significant behavioral issues, and at the end-stage of dementia or with very significant complications associated with diabetes.

LF: You’re describing a nursing home that is a lot more sophisticated in terms of the medical services they’ll provide and the health care professionals they’ll employ. Have you seen examples of this already?

VM: On the post-acute care side, they absolutely exist. I’ve seen people going directly from open heart surgery to a nursing home. All the time we see people after a hip fracture – pin placed, up walking. The next day they are in the nursing home getting rehab.

LF: In Massachusetts, the legislature set up a task force to look at the role of nursing homes in the LTSS continuum. It’s also looking at a closure process for nursing homes that reduces the impact on residents and employees, figuring out the role of nursing homes going forward. Do you have any advice for people who are tackling that problem?

VM: First, there’s probably not a lot that the state can do about this, other than ameliorate the consequences of a shift that’s going on. The shift is the function of changing preferences – people say they would rather die than go to a nursing home. If they have any money, they would prefer to go into an assisted living or something like that. The only thing the state could do would be to increase the payment rate, and thereby alter the dynamics.

LF: How so?

VM: Well, because if the payment rate were a lot higher, then you could operate with a lower occupancy rate.

LF: The shift in preferences you mentioned has been taking place for some time. How do you see it playing out in the future?

VM: Assisted living is a big force, but the even bigger force in terms of volume is people’s preference to stay in their own home for as long as possible. Demographically, the first baby boomer will hit 75 in a couple of years. Nursing home entry age is now 80, on average. Post-acute care starts at 75, goes to 85. Nursing home permanent placement, the age is 81, 82, and goes up to 100.

There’s a demographic shortfall of the generation prior to the baby boomers, the war years. There were fewer of them because of the Depression years. So there’s this funny little demographic nadir before the baby boomers hit with a big bump. The real wild card is the assets of the baby boomers. What proportion of them will be able to stay for how many years in assisted living, paying privately, before they need to go into a nursing home. That will play out in 10 to 15 years.

Leave a Reply