Craig Cipolla, graduated from UMB in 2005

Associate Curator of North American Archaeology, Royal Ontario Museum

Assistant Professor of Anthropology, University of Toronto

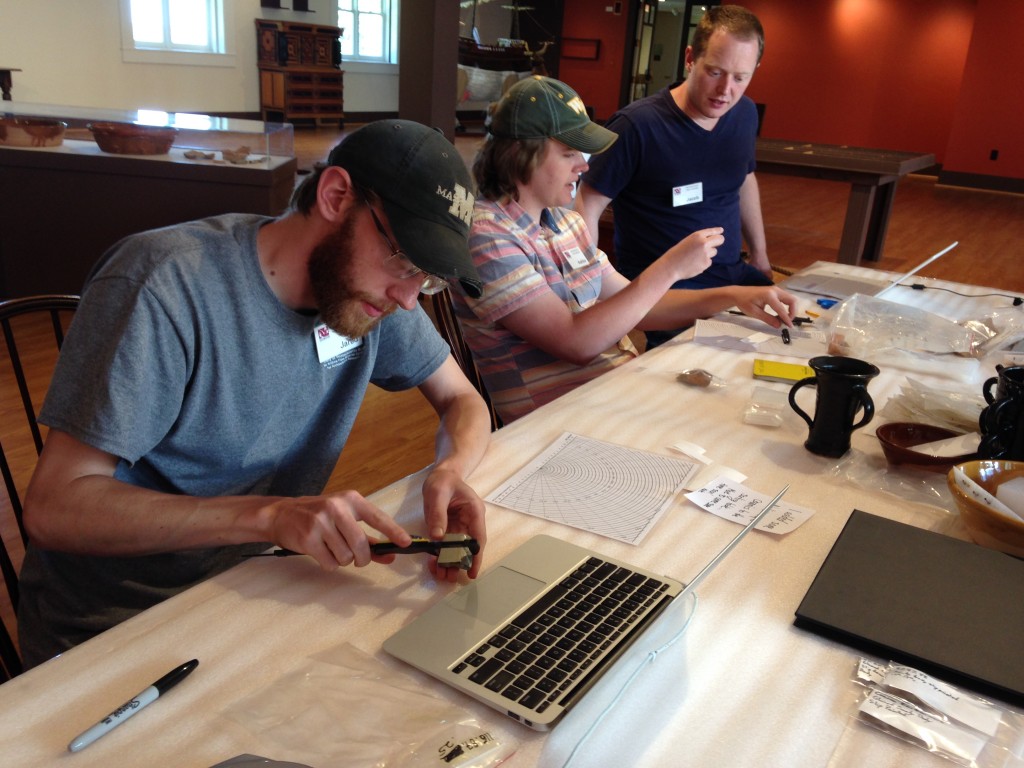

The Mohegan Archaeological Field School excavates an eighteenth-century domestic site, July 2015. This photo is from a forthcoming article by Craig Cipolla and James Quinn that will appear in the Journal of Community Archaeology and Heritage.

1. What is your position now; what do you do on a day-to-day basis?

I just started a new job as Associate Curator of North American Archaeology at the Royal Ontario Museum and Assistant Professor of Anthropology at the University of Toronto. My day-to-day consists of my own research, collections management, exhibits, and teaching at the University.

My research focuses on North American archaeology, particularly New England and the Great Lakes. My main interests include archaeological theory, material culture, the archaeology of colonialism, indigenous collaborative archaeology, heritage, and fieldwork. I direct an annual archaeological field school in partnership with the Mohegan Tribe of Connecticut and I look forward to the possibility of developing a field project here in the Toronto area at some point in the future. For now, my Toronto-based research will focus on the Royal Ontario Museum’s extensive collections.

Collections management consists of organizing and maintaining our North American archaeological collections, a large portion of which come from southern Ontario. I am responsible for working with outside researchers and First Nation groups who have interests in our collections. Essentially, I am responsible for archaeological assemblages amassed over more than a century. It is a huge responsibility.

Before joining the ROM, I was Lecturer in Archaeology and a Marie Curie Research Fellow in the School of Archaeology and Ancient History at the University of Leicester. There, I directed a Master’s Program in Historical Archaeology and the Centre for Historical Archaeology, an interdisciplinary research center devoted to the archaeology of the last 500 years. I taught courses in historical archaeology, North American archaeology, the archaeology of colonialism, and archaeological theory. I am excited to bring similar courses to the University of Toronto through my new position in the Department of Anthropology.

2. What is the most interesting project (field, lab, academic, or community) that you have worked on recently?

I love my work with the Mohegan Tribe. The project that I now direct in partnership with the Tribe is actually 20-years old (I began in 2010, just after finishing my Ph.D.). I truly believe that we have established an equal partnership that allows us to explore important new directions in collaborative indigenous archaeology and pedagogy. We are just beginning to publish some of the results so it is a very exciting time.

I’m currently finishing a book on contemporary archaeological theory (co-authored with Oliver Harris). It explores archaeological theory from about the year 2000 in language that is accessible to multiple audiences, including undergraduate students. We developed the project while teaching theory together at the University of Leicester. Generally speaking, it is a book that I’ve always wanted to write, so I will be thrilled to see it in print soon and use it in my teaching. The book is important because it will help to bring some of the more intimidating recent directions in theory (symmetrical archaeology, new materialism, material semiotics, and the ontological turn) into classrooms.

3. What is one thing that you remember specifically about your time at UMass?

This is too difficult a question. There is certainly much more than one thing! I suppose the most important skill set they offer at UMB is a holistic understanding of the research process. Their MA students really benefit from designing their own projects, implementing them in the field and laboratory, and writing them up. (This is the opposite of some “fast food” MA programs that exist in the world out there.) For my MA, I worked with a faunal collection from the Eastern Pequot Reservation. Within that one project, I delved into practice theory, faunal analysis, experimental archaeology, and even a bit of soil science. I eventually developed the project into conference papers and a few publications. I feel that my time at UMB—thinking through and experiencing the research process—allowed me to really hit the ground running when I began my Ph.D.

4. What is the best advice you got (or wish you had gotten) in graduate school?

Make sure you stay on schedule, but also take the time to enjoy your status as a graduate student. I did a terrible job at this, but I recommend building strong relations with your cohort and learning from them. Also, appreciate all that time you have to read!

For more alumni profiles, look here!