In the summer of 2015, University Archives & Special Collections at UMass Boston began to work with a number of area archival institutions to create “a digital library of material that can be widely disseminated for both curricular and scholarly use” related to the history of school desegregation and busing in Boston. And earlier this month, I participated in a panel at the Spring Meeting of New England Archivists about our efforts to make available archival materials related to school desegregation in Boston and about the work of educators to use archival materials in curricular settings.

View my presentation files and read a short essay based on my New England Archivist presentation here. For more information about this multi-archive collaboration, click here.

The process of selecting materials for digitization as part of this project was fairly difficult, as University Archives and Special Collections holds more than 200 linear feet of material related to Boston school desegregation. Too often, the history of Boston school desegregation seems weighted down by some of the most visible characters involved – politicians, policy-makers, court officials – so we decided early on to focus largely on identifying materials that tell a more complex, personal history of school desegregation and busing in Boston. After reviewing the range of materials in our care and the myriad rights issues involved, we decided to focus on two collections: the records of Mosaic, a program out of South Boston High School from 1980 to 1989, and the chambers papers of Judge Arthur Garrity, the federal district court judge who oversaw the Boston Schools case.

Mosaic was launched at South Boston High School in response to the effects of school desegregation. Led by professional writers and photographers, students produced stories and photographs about themselves and their communities. Eleven issues of Mosaic were produced, which include contributions from approximately 269 students at South Boston High and that address a range of topics, including immigration, homelessness, teen pregnancy, racism, work, and family. Explore the digitized issues of Mosaic here.

What’s particularly interesting about the chambers papers of Judge Arthur Garrity is the extent to which they do indeed tell some of the varied stories of those whose voices, in many ways, were marginalized throughout the desegregation process. By looking beyond one of the well-known characters in the Boston Schools case – the creator and a subject of this collection, Judge Garrity – we are able to begin to tell some of the more complex, personal stories of school desegregation and busing in Boston.

We digitized a number of materials from the Garrity papers, including the Judge’s correspondence with public officials and a full year of observer reports prepared by the Citywide Coordinating Council.

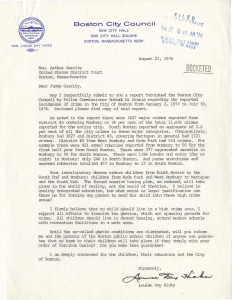

The correspondence we digitized offers an interesting window into the perspectives of people like Boston mayors Ray Flynn and Kevin White, as well as figures like Louise Day Hicks, the Boston City Councilor, School Committee member, and anti-busing activist. The correspondence also includes copies of letters to public officials from their constituents, as well as letters from the general public to Judge Garrity.

The Citywide Coordinating Council was established in 1975 to monitor implementation of the desegregation plan. Council observers were placed in schools throughout the city to report on activities within the schools. The reports required observers to complete a form noting different information about each school day, but what’s perhaps most intriguing about the reports are the descriptive assessments of the individual schools that observers provide. We digitized more than 400 daily observer reports from high schools around the city. View the digitized correspondence, observer reports, and other materials from the Garrity papers here.

We’ll be sharing more information about this project and these collections in the coming weeks and months. Visit blogs.umb.edu/archives for updates and information.

Please note: Some content in this post was drawn from my presentation at the Spring Meeting of the New England Archivists. See the presentation files and read a short essay based on that presentation here.

University Archives & Special Collections in the Joseph P. Healey Library at UMass Boston collects materials related to the university’s history, as well as materials that reflect the institution’s urban mission and strong support of community service, notably in collections of records of urban planning, social welfare, social action, alternative movements, community organizations, and local history related to neighboring communities.

University Archives & Special Collections welcomes inquiries from individuals, organizations, and businesses interested in donating materials of an archival nature that that fit within our collecting policy. These include manuscripts, documents, organizational archives, collections of photographs, unique publications, and audio and video media. For more information about donating to University Archives & Special Collections, click here or email library.archives@umb.edu.