On Wednesday May 30th the Hassanamesit Woods Field School crew officially broke ground at the Augustus Salisbury site and began the 2018 field season. This year’s focus is mainly on the 19th century Salisbury homestead, and the 18th-century Nipmuc deposits underlying the property. Under the careful direction of Dr.’s Mrozowski and Trigg, three undergraduate students and six UMass Boston graduate students have begun excavation of four 2x2m units.

On Wednesday May 30th the Hassanamesit Woods Field School crew officially broke ground at the Augustus Salisbury site and began the 2018 field season. This year’s focus is mainly on the 19th century Salisbury homestead, and the 18th-century Nipmuc deposits underlying the property. Under the careful direction of Dr.’s Mrozowski and Trigg, three undergraduate students and six UMass Boston graduate students have begun excavation of four 2x2m units.

Removing poison ivy from both the Augustus Salisbury and Deb Newman sites will be a major part of this field work, so the appropriate precautions are needed.

Graduate students Melissa and Liz are working closest to the poison-ivy

covered Salisbury foundation, and have thus both acquired their own personal bottles of Tecnu.

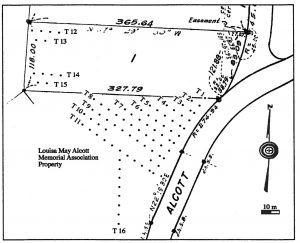

Graduate student Rick, whose thesis will be focusing on the changes in land use of this site and others in the surrounding area, is working with URI undergraduate Alex in the next unit over from the Salisbury foundation. UMass undergraduate Andrew is working with grad student Tyler in a unit with stunningly meticulous sidewalls, which lies in the middle of the focus area. Right next to them is UMass undergrad Bryn and grad student Gary (another student working on Hassanamesit Woods data for his thesis), who are working closest to the “Hawk Foundation”. Together these units run from the north of the site area, near the visible Salisbury foundation, to the south where the “Hawk Foundation” was discovered in a previous season. The area in between, covered by three of the units, is thought to be where the Nipmuc community of Hassanamisco may have built a meetinghouse and/or school. The hope is that by excavating these previously untouched middle units, the underlying Nipmuc sites may be identified, shedding more light on the physical erasure of Nipmuc land and community represented by the Salisbury site

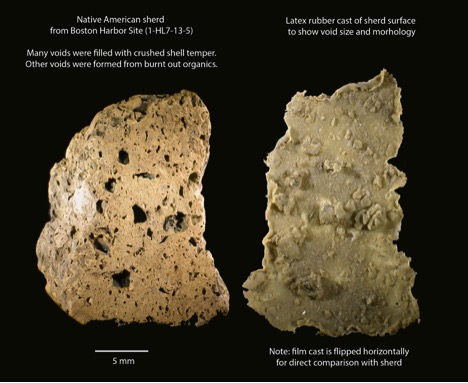

The students have been digging for two weeks now, however progress has been slow due to a deep layer of forest overgrowth and root mats. The site had to be cleared on the first day, necessitating many tick checks and poison ivy near-misses. Most objects coming out of the first few layers of the excavation units are architectural iron like nails and brackets, with small bits and pieces of ceramics here and there. Melissa and Liz are looking for a possible builder’s trench near the Salisbury foundation, while Rick, Alex, Tyler, Andrew, Bryn and Gary are all trying working down to the levels where Nipmuc sites may still be intact.

In the above photo, Gary, Dr. Trigg, Bryn, Alex, Melissa and Rick work to shade a cleaned and finished level within Gary and Bryn’s unit so it can be photographed for the site records. Photographing each level allows researchers to go back and look at the level-by-level changes in stratigraphy as a unit is fully dug down to the subsoil. Dr. Mrozowski can be seen in the background in his blaze orange jumpsuit, contemplating a previously excavated unit. After discussions with Dr. Trigg, and consulting the site paperwork, he decided to open up the older unit to follow a previously discovered feature that had not been fully excavated the past year.

But what about the sixth graduate student? Brian has been over at the Deb Newman site, not far from the Salisbury site excavation, trying to definitively locate her dwelling using a new application of metal detection. Brian has past experience with metal detection use in archaeology on battlefield sites, but noticed some patterns in his previous work involving domestic sites and the types of metal artifacts that produce positive results from metal detectors. Using this method he is carefully covering the area around the Deb Newman site, and is marking out areas for later excavation. It is expected that some of the students currently at the Salisbury site will soon move over to the Newman site to begin further excavations there.

All in all it’s shaping up to be an exciting month of excavation at the Newman and Salisbury sites at Hassanamesit Woods, and we’re looking forward to updating you on the progress we make.