By Jacob deBlecourt

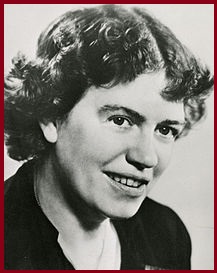

Since the Brothers Lumière premiered their Cinematographe in 1895, questions have arisen as to exactly how to use the medium of film to its greatest potential. Are films simply a product for entertainment? Are films better than the written word? Do they have academic merit? Though the answers to these questions may never be agreed upon unanimously, the field of anthropology seems to have found a use for the visual medium. As Margaret Mead writes in Visual Anthropology in a Discipline of Words, “as finer instruments have taught us more about the cosmos, so finer recording of these precious materials can illuminate our growing knowledge and appreciation of mankind.” The use of film as a medium of anthropological documentation has been increasingly used over the course of the past several decades.

Thanks to the work of anthropologists like Margaret Mead, film in anthropology has become increasingly more important, serving as a medium which helps to educate the general viewing audience.

In addition, it also makes it easier for anthropologists to document their findings, and helps solidify the medium of the documentary film in anthropology as objective in a time when the distinction between objective and subjective is skewed.

Anthropological films help audience members visualize the cultural aspects of various peoples. In doing so, it allows for greater accessibility. Perhaps to the disdain of some anthropologists, written publications and lectures on anthropology can sometimes be so academic that it inhibits people’s understanding of the subject. Though colloquial, there is value to the phrase “a picture is worth a thousand words” in the field of anthropology. In other words, as John Weakland described in Feature Films as Cultural Documents, “beyond content itself, anthropological film studies may extend to other matters that relate to ordinary evaluative viewing: how do films relate to their cultural sources? What is their cultural function and influence? Do films illuminate more general cultural patterns?” Perhaps what is most important about that quote is the last question. The field of anthropology itself is dedicated to identifying uniquely human traits in various societies in an effort to note common patterns between those groups of people. Weakland makes the argument that films, specifically feature anthropological films, allow for the possibility for lei persons to ask the questions that the greatest anthropologists are asking themselves.

Nanook of the North is considered to be one of the most significant anthropological documentaries, despite its glaring inaccuracies.

Margaret Mead championed the use of film in anthropology in part because it allowed for greater accessibility to a viewing public. In Visual Anthropology in a Discipline of Words, she describes the cinematic works of some anthropologists to be “magnificent efforts.” A great example of the effort to have the general population ask anthropological questions would be with Margaret Mead’s 1950 documentary Four Families in which she, on screen, dissects the differences and similarities from four culturally distinct families—one Canadian, one French, one Japanese, and one Indian. The film has a meta-structure in that it depicts Mead on screen watching the anthropological documentaries as she comments on them. Mead’s observations could have very easily been written down in a book, but instead she used the medium of film to supplement her findings with depictions of what she describes. This way, the audience can hear Mead speak academically about the four families while visualizing those comments.

As much as the use of film in anthropology has benefited the public, it has perhaps benefited the anthropologists themselves even more. Before the introduction of film to the field of anthropology (and still to this day), anthropologists usually relied on two tools: a pencil and a piece of paper. The lack of technology and resources made it difficult to accurately and completely record the aspects of peoples’ cultures. As Margaret Mead puts it, “the fieldworker had to rely on the memory of the informant rather than upon observation of contemporary events.” Documentaries such as Divine Horsemen, a film about the Haitian Voodoo rituals involving dance and music, would be far more difficult to capture in words than it would be to simply show the dances and music.

In addition to anthropologists benefiting from the medium of film intellectually, they also benefit artistically. While anthropologists remain objective, emphasizing the significance of particular cultural traits in a society is enhanced with artistic editing and storytelling. For example, in Robert Gardner’s Dead Birds, the Dani people are studied from the perspective of two protagonists—one young, one older. The younger one, Pua, desires to have the responsibilities of the adult men: he wants to farm, to fight, and to feel strong. Weyak, the adult, has these responsibilities, yet experiences them entirely different from Pua’s fantasies. After a village child is killed by an enemy tribe near Weyak’s surveillance outpost, the viewing audience sees the weight of those responsibilities when not carried out. Gardner uses the dichotomy of the young and the old to help explain how the Dani people understand age and responsibility to the tribe. As John Weakland put it, “even real life involves the conceptualization, organization, and punctuation of experience.”

The artistic effect on anthropological films can also be seen in feature presentations. Eric Steel’s The Bridge beautifully contrasts the striking allure of the Golden Gate Bridge with the tragically large number of suicides which takes place on it.

At this point, there needs to be a division made between the significance of anthropology on film and the significance of anthropologists on film. The impetus to understanding this difference lies partly with the answer to the question: What is a documentary? A documentary is not necessarily non-fictional; television shows like Documentary Now! as well as films such as Best In Show use the moniker of “mockumentary,” a film designed like a documentary but is entirely fictional. A documentary is also not necessarily objective, either. Films such as Triumph of the Will, a Nazi-era documentary, ostensibly use the intellectual authority of a factual documentary, but in reality are carefully compiled so as to propagandize an unknowing population. In essence, then, a documentary is simply any information, true or false, presented in a factual matter. This can be troubling for objective anthropologists who rely specifically on the genre of documentary to present factual information. Emilie De Brigard describes this trend, giving the example of the social documentary film, which she describes as “a mass education medium sensitive to the needs of government policy….If the explorer film cannot escape its exploitative nature, neither can the documentary desist from visionary exhortation.” This is important because moviegoers can see the work of objective anthropologists as equally deserving of the handle “documentary” as a film whose authors had skewed motives.

Even films claiming to be of anthropological value have raised questions of accuracy and ethics.

Robert Flaherty’s Nanook of the North famously used staged actors. At the Winter Sea Ice Camp even went as far as to construct phony igloos for the natives to use. Because the work of the objective anthropologists is grouped with skewed and undisciplined entertainment or political films, the value of anthropologist’s objectivity is wasted. This essay then, is not so much a statement on the importance of film in anthropology, but a defense of the intellectual worth of these anthropological studies. By maintaining their authority and their ethos in the documentary genre, anthropologists are able to continue their work of actualizing the unique human traits which connect all societies and peoples.

In response to concerns over the authenticity of presented information, anthropologists have compiled a set of guidelines which they follow when producing films, known as the Rules for Film Documentation in Ethnology and Folklore. As Brigard describes it, “these rules require that filmmaking be done by persons with sound anthropological training or supervision, and that an exact log be kept.”

Though film in anthropology was often a secondary resource, its ability to offer accessible understanding of cultures to a general audience has invigorated academics and lei people alike. By allowing anthropologists to focus on key aspects of the culture as a means to convey greater understanding of the culture as a whole, film has given anthropologists more flexibility when it comes to presenting their work. Anthropology on film has also made observing cultures more accurate, substituting the pen, paper, and word of mouth with contemporary footage. Perhaps most importantly, anthropology on film provides the opportunity to distinguish factual, objective studies from propaganda or misinformation. Provided that anthropologists can find an ideal way to ensure objectivity and factuality in their films, the medium of cinema in anthropology should be able to plant its significance in the academic and untaught worlds. With this in mind, it is evident that film in anthropology is crucial to its core mission: understanding the greater human culture as a way to make discoveries of our own humanity.

Links to Referenced Material:

- Visual Anthropology in a Discipline of Words

- Feature Films as Cultural Documents

Fascinating article. It was a great read.