Gordon Sato (left) with interviewer Dr. Paul Watanabe, 2011. Gordon was incarcerated at the Manzanar War Relocation Center and attended Central College in Pella, Iowa.

Author: Shay Park, Archives Assistant

You know, we studied civics in high school and when I realized that the government was interning these American citizens and putting them behind barbed wire, I just could not believe it. It was not American, not the United States that I knew. —Esther Nishio, former Pasadena College student and former prisoner at the Granada War Relocation Center

During World War II, President Franklin Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, which authorized the removal of anyone living in vaguely defined “military areas.” These areas were largely located on the West Coast, where Japanese immigrants had settled and developed thriving communities since the turn of the twentieth century. These residents were regarded with suspicion by government officials and other Americans as potential threats to the United States solely on the basis of their national origin. Thus, by declaring the West Coast a “military area,” these Japanese and Japanese American residents were deliberately targeted, though not explicitly named, in FDR’s Executive Order (1).

The policy of removal and relocation to internment camps lasted from 1942 to 1945 and imprisoned nearly 120,000 people. The majority of those incarcerated were American citizens and were held without evidence or due process. The evacuations began on March 24, 1942, and internment continued until a 1945 Supreme Court decision ruled the practice unconstitutional. The last camp closed in March 1946 (2).

Alice Takemoto, 2011. Alice was incarcerated at the Santa Anita Assembly Center and Jerome War Relocation Center and attended Oberlin College in Ohio.

The holdings in University Archives and Special Collections in the Healey Library at UMass Boston includes the digital collection “From Confinement to College: Video Oral Histories of Japanese American Students in World War II.” The collection contains video interviews, transcriptions of those interviews, and photographs of the eighteen participants interviewed for the oral history project. All eighteen are Japanese Americans who were relocated to internment camps. The project was carried out by the Institute for Asian American Studies at UMass Boston and the interviews were conducted by Dr. Paul Watanabe in 2010-2011.

The interview subjects describe the living conditions at sites that typically consisted of buildings not intended for human habitation, most often horse stalls in large barns, that offered little privacy or comfort. Unsurprisingly, many of the interviewees describe a “block” or “blank” in their recollections of that time, but some are able and willing to recount aspects of their daily lives, such as the jobs they worked in the camp’s cafeteria or as maintenance workers, or the games and activities they participated in with their families and friends in the camp to pass the time.

What is remarkable about these former prisoners’ experiences is that they attended college during the period of Japanese internment. They were all roughly aged 16 to 20 at the time of evacuation, and soon after arriving at the camp, it was arranged to have them attend university. This was typically accomplished by several people working together, such as their parents, other acquaintances in the camp, and/or individuals and advocacy groups outside the camp. Several of the interviewees described themselves or their families as having a natural expectation that they would still go to school, despite the unnatural circumstances in which they found themselves.

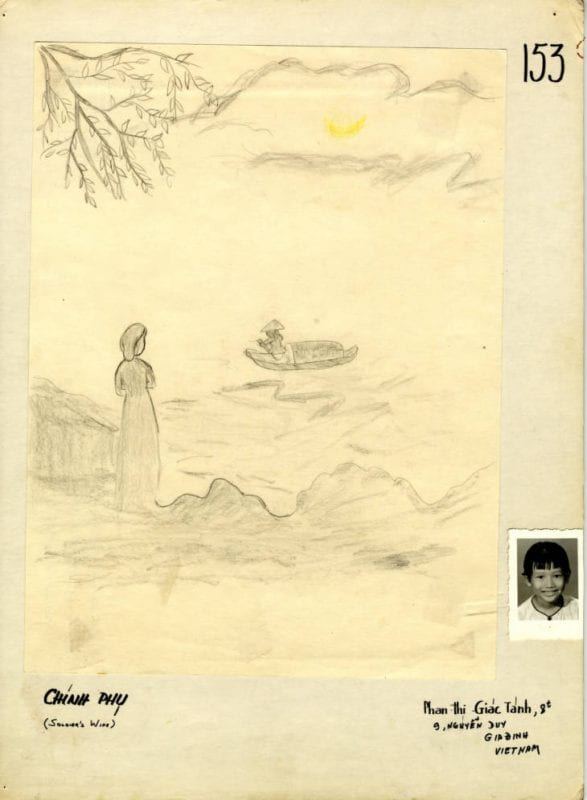

In order to cover the costs of living and tuition, most of the interviewees became live-in maids or nannies for local families near their new university. These arrangements were also facilitated by others on their behalf. Several of the interviewees cite Quaker groups or organizations like the National Japanese American Student Relocation Council or Friends of the American Way as providing instrumental help through the process of applying, moving, and locating a place to live and work.

Frank Inami, 2011. Frank was incarcerated at the Fresno Assembly Center, Jerome War Relocation Center, and Rohwer War Relocation Center, and attended the University of California, Berkeley.

There were instances when community members learned that an interned Japanese American person would be attending a nearby university and held protests in response. The most notorious incident happened to Esther Nishio, one of the interviewees and the first Japanese American student to attend a California university after internment. Her arrival at Pasadena Junior College was met with harassment and in some cases violence. Esther says in her interview with Dr. Watanabe that she was mostly insulated from the “furor,” but Pasadena community members harassed Esther as well as school officials (3). Other students were forced to change universities before they even arrived because of the uproar their admission caused, or the school rejected their application outright. And even when they were able to attend, in some instances the locals treated them with hostility.

However, even in cases like Esther’s, many of the interviewees describe a welcoming environment from classmates, teachers, and administrators within the university itself. Esther described her fellow students as “very friendly”: “[T]hey were all so wonderful to me… I met soldiers who had returned from the South Pacific who were attending college and… they couldn’t be nicer. It was just these other people that were causing so much problems.” Most said they were one of very few Japanese American students at their university, but despite that, they felt accepted and even enjoyed their time. “I had no trouble fitting in, really,” said Chiye Tomihiro. “You know, I went to a school in the first place in Portland where, you know, I was a minority to begin with so… it wasn’t something new for me.” Similarly, Francis Fukuhara called his transition into the student population “seamless” and Theodore Ono described the reception as “very kind and warm.”

The interview subjects majored in a variety of fields, ranging from math and science to art and music, and studied at universities throughout the country, such as Oberlin College, the University of Denver, and the University of Missouri. Following the war and their time in school, they went on to live interesting lives as teachers, scientists, artists, and more. Some of the notable figures interviewed for the project are George Matsumoto (1922-2016), a Modernist architect, Gordon H. Sato (1927-2017), a prominent cellular biologist, and Setsuko Nishi (1921-2012), an activist, sociologist, and professor who taught the first Asian American studies courses at City University of New York (CUNY).

Setsuko Nishi, 2011. Setsuko was incarcerated at the Santa Anita Assembly Center and attended the University of Southern California in Los Angeles and Washington University in St. Louis, Missouri.

In what is already a strange and contradictory tale—Japanese American students who left imprisonment to attend school in a country that considered them and their families potential enemies of the state—there are more twists: some of interviewees were drafted to fight in the war during their internment, and a few even went on to work in national security. Participant Robert Naka recounts the surprise he felt when he was granted clearance to work on a government contract that involved working on radar detection of bombs. He then went on to become deputy director of the National Reconnaissance Office (a part of the United States Department of Defense) in 1969. Robert remembers a conversation he had with a colleague later about these experiences:

We talked about [my time in the internment camp] and then he said, “Gee, Bob, you went from being a distrusted American to one of the most trusted we have. You ran the National Reconnaissance Office. That was a tightly, tightly held secret of the United States government. And you signed papers to the White House with all these tightly held code word classifications on the letter and it’s truly remarkable.” And he said, “Only in America could such a transition possibly be allowed.” He thought it was incredible and so did I.

“Only in America”—it is a sobering remark on what Robert and the tens of thousands of other prisoners experienced during World War II under the policy of the US government. But Robert, like several of the other interview subjects, chooses to view what he went through with a hopeful lens. When asked by Dr. Watanabe what lessons he would want other to take away from this history, he replies:

Well I can only continue with this notion of “Only in America.” …It’s an amazing arrangement of a democracy where a person has considerable individual freedom and roadblocks occur… but the society is permissive so that you can actually work your way around and through these difficult periods and make contributions to our society.

This hope Robert and others feel based on their ability to persist is joined by a hope rooted in the ability to share their stories. “I don’t know [what] else we can do except tell our stories. …[M]aybe leave a legacy, for the others to follow,” says Rose Yamauchi. She continues, describing about her efforts to write about her experiences in a writing group:

I was unable to talk about it for years. I don’t know why, just, we didn’t talk about it.… Of course we were busy working and trying to build careers and things, but still, it was an experience that maybe we wanted to forget, I don’t know. Anyway, we might still have held a grudge for a long time, I know, because when I started to write the stories, that is the first time I was able to put it on paper or able to talk about it and my friends in the writing group realized that too, that when I first started writing, I couldn’t get up and read the story even. But gradually it’s gotten easier…

“You know you can tell by the way that a person responds what kind of person they are. It’s amazing,” Rose concludes. “They respond well to it and I, in turn, I am able to take the burden off of my soul and tell the story of my internment and my life.”

The oral histories document a broad range of experiences of internment based on gender, geography, class, and more. To view the video interviews or read the transcripts, visit the collection here. To learn more about Japanese American college students who experienced internment during World War II, see below.

References

1. “FDR orders Japanese Americans into internment camps.” History, https://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/fdr-signs-executive-order-9066.

2. “Japanese Internment Camps,” History, https://www.history.com/topics/world-war-ii/japanese-american-relocation.

3. Mozingo, Joe. “She was a test case for resettling detainees of Japanese descent—and unaware of the risk.” LA Times, 30 November 2019, https://www.latimes.com/california/story/2019-11-30/column-one-she-was-a-test-case-for-resettling-detainees-of-japanese-descent-and-unaware-of-the-risk.

Further reading

Articles:

Austin, Allan W. “National Japanese American Student Relocation Council.” Densho Encyclopedia, http://encyclopedia.densho.org/National_Japanese_American_Student_Relocation_Council.

—. “American Friends Service Committee.” Densho Encyclopedia, http://encyclopedia.densho.org/American_Friends_Service_Committee.

Bigalke, Zach. “World War II and the National Japanese American Student Relocation Council.” Blog post. Unbound. The University of Oregon, Special Collections and University Archives, 23 January, 2015, https://blogs.uoregon.edu/scua/2015/01/23/world-war-ii-and-the-national-japanese-american-student-relocation-council.

“Courage and Compassion: Student Biographies.” Oberlin College and Conservatory, https://www.oberlin.edu/courage-and-compassion-student-biographies.

Erlandson, Devin. “The Relocation of Japanese American Students to Wayne University during World War II.” Blog post. Walter P. Reuther Library, Wayne State University, 11 July 2014, http://reuther.wayne.edu/node/11936.

Books:

Austin, Allan W. From Concentration Camp to Campus. University of Illinois Press, 2004. https://umbrella.lib.umb.edu/permalink/f/1951nkk/01MA_UMB_ALMA51217089110003746.

Okihiro, Gary. Storied Lives: Japanese American Students and World War II. University of Washington Press, 1999. https://umbrella.lib.umb.edu/permalink/f/1951nkk/01MA_UMB_ALMA51158086030003746.

Takemoto, Paul Howard. Nisei Memories: My Parents Talk about the War Years. University of Washington Press, 2012.